A Proposed New Comprehensive Model of Consciousness and Emotion

❝Part One - The neuro-anatomy and associated neuro-physiology of the core components of memory, emotion and motivation, by Ian Weinberg | Practicing neurosurgeon❞

Therapy should be personal. Our therapists are qualified, independent, and free to answer to you – no scripts, algorithms, or company policies.

Find Your Therapist

Introduction

Ongoing research in neurophysiology has resulted in the convergence of multiple neurological and neuropsychological concepts into an integrated holistic model. By employing such modalities as fMRI spectroscopic scanning, PET and SPECT scanning as well as electroencephalography we are witnessing significant breakthroughs in the understanding of the core processes of the human brain. Although the observed neurological processes are complex, it is still possible to discern relatively simple functionality supported by defined areas and their connections. In this regard we are now able to identify the neuro-anatomy and neuro-physiology (including neuro-chemistry) of such fundamental functions as memory and recall, emotion and motivation. In this article, part one (

click here for part two

), the relevant neuro-anatomy will be described initially. Thereafter the core components of memory, emotion and motivation will be defined in the context of neuro-anatomy and associated neuro-physiology.

Overview of the anatomical components and their functions

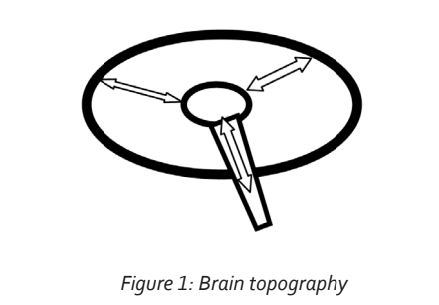

All neurological activity is based on the function of the neuron. Neuronal integration occurs as a result of the propagation of electro-chemical activity along neuronal processes (axons and dendrites), which then stimulate the adjacent cell or process at the synapse. The synapse represents a chemical bridge that connects the activated neuron or process to the next cell. The chemical released into the synaptic cleft is referred to as a neurotransmitter. Simplistically, the brain can be regarded as a sphere surrounding a central core of cells or nuclei from which a stem originates. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

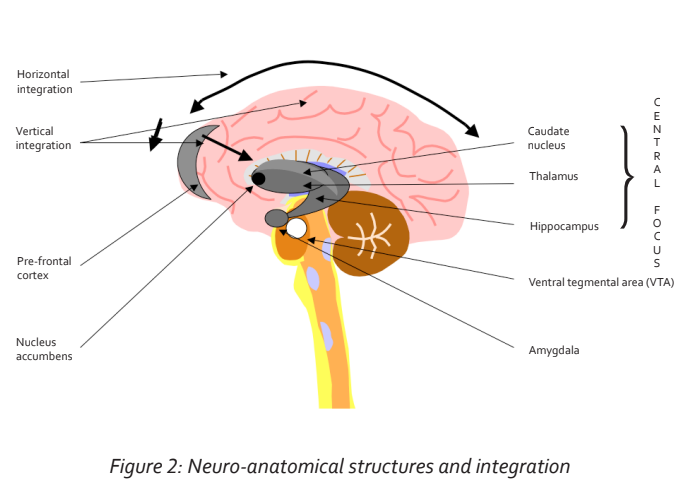

The circumference comprises the cortex. This incorporates all the primary sensory areas, the areas receiving sensory information such as vision, hearing, touch and smell, as well as their related association areas. This is defined in more detail below. All the information represented in these cortical areas is integrated or connected and all project to the very front of the cortex, to the area referred to as the pre-frontal cortex. The pre-frontal cortex is the seat of such functions as concentration, motivation and working memory (Arnsten, 2009). Working memory is an abstract process in which sensory, sensory association and other integrated information is further integrated to a higher level. The processes taking place within the pre-frontal cortex are referred to as executive functions. In this way the pre-frontal cortex may be regarded as the driver of conscious action.

The entire cortex projects to the deep nuclei, specifically to the thalamus. This projection is a two-way connection. We are therefore able to define two projection or connection configurations: circumferentially through the cortex (termed the horizontal integration); and from the cortex to the deep structures (termed vertical integration). See Figure 2.

The thalamus also receives connections from the brain stem, which represent sensory fibre connections from the entire body.

The thalamus in turn conveys motor connections through the brain stem to the entire body. In this respect we can regard the thalamus as being a major relay station connecting all motor and sensory fibres from the brain to the entire body (Percheron, 2003). But the thalamus is functionally more than just a relay station. It represents the central focus of cortical activity with major representation of the pre-frontal cortex (fronto- thalamic tract). We can, in fact, view the thalamus as the screen of consciousness—the place where our subjective consciousness resides. The thalamus is well connected to the hippocampus. The hippocampus supports important short-term memory functions, as well as contextual (spatial) memory. This connection logically promotes the memory and storage of information screened at the thalamus.

Without the active input of the hippocampus, screened information at the thalamus would disappear after momentary projection, very much like RAM in a computer— the memory disappears when the computer is switched off.

The thalamus is also connected to emotional centres. The two important areas are the amygdala, which supports fear, anxiety, panic and anger and is also associated with emotional memory, and the nucleus accumbens, which is the centre supporting pleasure and gratification (Amunts et al., 2005). In fact, as will be discussed below, all other emotions are derived from an interplay of these two emotional centres.

Movement co-ordination is supported by other deep nuclei termed the basal ganglia, which also connect to the thalamus. In this way, screened information, mainly from the pre-frontal cortex, motivates movement. The neurotransmitter for movement in the basal ganglia is dopamine. This is produced in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the brainstem and functions as a neurotransmitter in the basal ganglia. When dopamine production diminishes, Parkinson’s disease may develop. This is essentially a movement disorder but often has an associated cognitive dysfunction, possibly reflecting a degeneration of connections to the thalamus and pre-frontal cortex. Dopamine originating in the VTA is also conveyed to the nucleus accumbens, where it is the mediator of pleasure and gratification. Dopamine is also the mediator in the hippocampus and in the caudate nucleus, another of the deep nuclei that is involved with procedural memory and learning and which has a strong connection to the pre-frontal cortex. Already, at this stage we note the integration of memory, learning, motivation and pleasure/reward through a common neurotransmitter, dopamine (Packard & Knowlton, 2002).

Horizontal Cortical Integration

The initial growth configuration of axonal and dendritic processes of the neuron in the embryo reflects genetic influences. With further maturation, environmental factors begin contributing to this hard-wiring phase of neuronal development with a progressively increasing influence. It has been shown, for example, that maternal hormones, notably cortisol, cross the placenta and influence neuronal development. This is discussed in more detail below.

Reviewing the hard-wired configuration at the level of the primary and secondary sensory areas, as well as at the level of association, it becomes apparent that neuronal cells and collections of neuronal cells are stereotypically, spatially arranged for function. The areas most clearly demonstrating this arrangement are the visual and auditory cortices. In effect, the sensory process at the cortical level is characterized by the fragmentation of the incoming signal into its most fundamental components. In the visual cortex, the incoming light signal is fragmented to a level at which first order receptive cells respond only to fixed points of light frequencies or darkness. Thereafter subsequent order cells higher up in the filtering hierarchy begin synthesizing the sensed information received from the lower order cells through specific receptivity to further qualities of the sensed signal such as static and moving lines in all angles of orientation (Ganong, 1979). The information is further filtered through progressively higher order neurons which are individually responsive to more qualities of the sensed signal and in this way begin to synthesize the perceived information (Felleman & Van Essen, 1991). This process continues until it arrives at a point where the cells at the apex of this filtering and re-synthesizing hierarchy are the representation of the perceived entity. It is postulated that this apical representation is most likely situated in an association area. This sensory-association process may be summarized as follows:

1. First order cells receive the incoming sensory information in a fragmented form.

2. A hierarchy exists such that the sensed information is transferred through successive orders of cells, each being responsive to more of the features of the sensed information than the preceding order.

3. The configuration of all the cells is stereotypically arranged to carry out this required function.

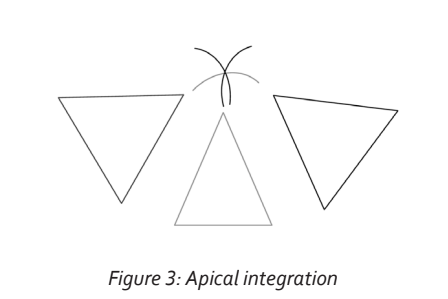

4. The overall configuration of participating cells is triangular (pyramidal or conical in three dimensions) in that the base comprises the greatest numbers of cells, each specific only to very small increments of sensed information, while higher orders comprise progressively fewer cells, each specifically representative of more information. The least amount of cells would be situated at the apex of the configuration—the specific representation of the sensed entity.

This process represents the labeling of individual entities in the environment. Once a foundation of labeled entities is established, the process continues with the integration of associations of labeled entities. In this way awareness evolves into understanding that ultimately contributes to the development of pre-frontal lobe qualities.

Creativity

The hard-wired process described above will give rise to an adequate integration, supportive of human consciousness and independent function. This represents a common foundation, stereotypically similar for all individuals. We deduce this from the observation that neuro- anatomy and neuro-physiology are similarly spatially localized in different individuals. At this point we would need to project further in terms of this integration process to provide a model supportive of individual creativity. In order to explain creativity, we would need to expand the hard-wiring beyond the apices of primary triangular configurations, specifically representative of entities and their associations. In effect, hard-wiring represents an integration of environmental entities and their associations. Creativity, on the other hand, reflects a future-based, abstract integration.

We can assume that many “un-labeled” neurons and processes exist within the milieu of the integration process. These neurons would provide the substrate for further integration. In the event that the apices of two or more representative triangles of configuration are triggered, neighboring neurons and their processes may be recruited and incorporated in the synaptic circuit. In effect, the recruited neurons, termed inter-neurons, would be those caught in the common penumbra of triggered apices. This is illustrated in Figure 3. This process would be more likely to occur if the triggering were repetitive and if there was an element of reward (dopamine-based). As in all neuronal circuit creation, the initial neuro-transmitter mediated connection would evolve into a structurally permanent circuit through protein synthesis and axonal/dendritic growth (Kandel, 2001). The integration of apices elevates neuronal association to a higher order. The expansion of consciousness is therefore a consequence of repeated integration of subsequent apices of representation. The process of recruitment of substrate inter-neurons and the elevation to a higher level of apical representation appears to be co-ordinated in the anterior part of the non-dominant superior temporal gyrus (Jung-Beeman et al., 2004). Activity in this region is associated with thegeneration of a burst of gamma EEG frequency—the ‘aha’ moment.

The Basis of Memory Storage

Memory refers to the stored information that has resulted from the integration process. The function of memory recall depends on a logical and efficient storage configuration. Two broad categories of memory have been defined: Memory that can be consciously recalled is referred to as declarative memory, while memory associated with complex motor activity (procedural memory), and that related to emotion (emotional memory), cannot be recalled in terms of individual components. This latter memory function is referred to as non-declarative (Davachi & Dobbins, 2008). Declarative memory recall is initiated by the dorso-lateral regions of the left (dominant) pre-frontal cortex while non-declarative emotional memory recall is initiated by the ventro-medial pre-frontal cortex, predominating on the right side. The hippocampus is the structure associated with declarative memory, while the basal ganglia and amygdala support procedural memory and emotional memory respectively.

The key to understanding the process of memory storage is the appreciation of the interplay of genetic expression with activated, stereotyped neuronal cells. It has been shown that primordial neurons differentiate in response to genetically determined induction factors. Of significance in this regard is the finding that neuronal differentiation is dependant upon location within the developing neural tube. Following differentiation, neuronal cell processes migrate to specifically predetermined destinations under the influence of cell-derived guidance factors (Jessell & Sanes, 2000). From these observations it can be extrapolated that neuronal populations are stereotypically configured in terms of theiranatomical location to represent specific functions or bytes of information. The initial stimulation of a given neuron occurs therefore as a result of the location of the neuron within an integration, which is genetically determined. The configuration of synaptic connections is also genetically determined. Consequently a given neuron and its connections, when stimulated, immediately represents a pre-programmed byte of information. The genetic transcription of prion-like proteins to establish permanent synaptic= connections completes the hard-wiring process (Si et al., 2003). In this way memory storage is a product of precise, stereotyped neuro-anatomical location and the subsequent transcription-driven imprinting and labeling of the neuron when triggered with a byte of information appropriate for that specific neuron within the integration. In other words, a given neuron represents a convergence point for specific representation of information by virtue of its genetically determined, stereotyped anatomical location and its position within a synaptic integration.

It follows that the loss of neuronal cells and consequently the bytes of memory incorporated within them, would not necessarily diminish the information stored within the greater configuration. More integrated neurons higher up in the configuration that have been activated and imprinted with information would incorporate the information represented by lower tier cells. Evidence in favor of this postulate is the finding that the removal of the first order visual cells (decortication) in the monkey does not result in an appreciable loss of visual discrimination. Clearly, higher order levels of representation had been imprinted with lower order information (Keating & Horel, 1972).

The horizontally integrated information projects to the thalamus via the vertical cortico-thalamic integration and thereby brings to awareness the information represented by the specific neuronal component of the integration. It is postulated that every cortical apical neuronal representation is represented at the thalamic level. This anatomical arrangement achieves a more rapid and efficient screening of stored information, including newly integrated apices, at the central focus. In effect, appropriate apices of representation are retrieved via both the existing cortical (horizontal) integration, as well as by radial projection to the thalamic central focus. As indicated previously, it is the hippocampus which is required to facilitate memory and recall of information screened at the thalamus. In this context it is postulated that the hippocampus maintains connections to all radial, cortical projections. In order to facilitate its memory and recall function, the hippocampus would need to incorporate a precise spatial-contextual mapof representation of the entire cortical neuronal integration. In support of this function has been the finding that taxi drivers in London, who store vast amounts of spatial information, have markedly enlarged hippocampi (Maguire et al., 2000).

Emotional Centers and Connections

The two defined emotional centres are the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens. A significant proportion of emotional activity reflects the interplay of these regions. The amygdala supports fear, anxiety, panic and anger and plays a major role in emotional memory (Gorman et al., 2000). When stimulated, it activates its connections to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and to the locus ceruleus,resulting in the secretion of cortisol and noradrenalin respectively. The secretion of noradrenalin, together with adrenalin, initiates the sympathetic response. The sympathetic response is manifested by a rapid heart rate, increased blood pressure, sweating and an increased respiratory rate. These are all the physiological changes seen in the anxiety or panic state. These changes also occur in response to hypoglycaemia, hypoxia and pain. It is postulated, therefore, that these states in the neonate trigger and integrate the hard wired amygdala, thus establishing fear and its manifestations. Theraised cortisol levels associated with the activated amygdala have far reaching effects on immune function and general metabolism. Finally, the amygdala projects to the thalamus and thence to the pre-frontal cortex and also directly to the pre-frontal cortex thus integratingthe fear or anger emotion with conscious perception. Reciprocal connections from the pre-frontal cortex, as well as connections from the hippocampus to the amygdala, serve to modulate (stimulate or suppress) the emotions supported by the amygdala. fMRI studies have revealed that the activated right pre-frontal cortex suppresses amygdala activity. In this way it can be appreciated that if amygdala function is modulated by pre-frontal activity, the individual is in a reflective mode. If, on the other hand, fight or flight behavior manifests, reflecting unmodulated amygdala activation, the individual is in a reflexive mode (Arnsten, 2009). Recent studies have revealed a connection between the nucleus accumbens and the amygdala. Following deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens, significant diminished metabolic activity was noted in the amygdala. Clinically this manifested as antianhedonia with anxiolysis (Bewernick et al., 2010).

Cortisol stimulates amygdala function (Chrousos & Gold, 1998). In this way a positive feedback phenomenon occurs in that cortisol stimulates the amygdala, which in turn increases cortisol secretion (via the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus). Recent studies have shown that high levels of maternal cortisol in a stressed, pregnant woman cross the placenta and sensitize the amygdala of the developing fetus. This appears to promote an excessive fear and/ or anxiety component in the new born infant in response to stressors (Van den Bergh et al., 2005). The problem may be compounded if the new born infant is exposed to nurture deprivation (Coplan et al., 1996). Raised levels of cortisol occur in the new born infant in response to stress, but diminish when adequate nurture levels are maintained. If nurture is inadequate or interrupted, levels of cortisol remain high and continue to sensitize the amygdala, thus amplifying fear and anxiety. Studies have also shown that children who were exposed to chronic deprivation such as occurred in orphanage institutionalization have raised cortisol levels in the later part of the day (Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006). A percentage of adults who were maltreated as children were shown to have decreased cortisol levels in response to stress. This finding is difficult to explain but may reflect an adrenal fatigue pathophysiology.

Chronically raised levels of cortisol have also been shown to disrupt hippocampal function (McEwen, 1998). Consequently, short term memory, contextual memory and memory recall may be impaired. If raised cortisol levels persist, hippocampal cells may degenerate and die off with resultant hippocampal atrophy. This is observed on MRI scanning. Timely intervention however has been shown to halt and even reverse the process. Finally, chronically raised cortisol levels suppress cell-mediated immunity (natural killer cell activity), which may result in a state of immunosuppression.

The nucleus accumbens is the seat of pleasure and gratification (Zahm, 2000). The mediating neurotransmitter is dopamine. Substantial connections exist between the nucleus accumbens and the pre-frontal cortex. The mediating neurotransmitters in the nucleus accumbens-frontal connection include both dopamine and noradrenalin. The nucleus accumbens is activated when sensory pleasure, reward and achievement are experienced or anticipated. Drugs such as cocaine, amphetamines and opiods stimulate the nucleus accumbens, eliciting subjective pleasure. Physiological activity such as eating, exercise and orgasm are also associated with raised dopamine levels. The subsequent activation of the pre-frontal connection results in a heightened focus and concentration. The caudate nucleus, a deep nuclear structure close to the thalamus and nucleus accumbens, is an important memory centre with projections to the pre-frontal cortex. It appears to be specifically involved with feedback memory. Neurotransmitter mediation in the caudate nucleus and in the projecting fibres to the pre-frontal cortex is via dopamine. Studies have shown that reward-activated nucleus accumbens activity appears to enhance memory and learning as supported by the caudate nucleus, mediated by dopamine (Olds & Milner, 1954).

The complex interactions between the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex have been elucidated through several studies. Stimulation of the amygdala in rats resulted in suppressed activity of the dopaminergic system in the nucleus accumbens. This was mediated by suppressive glutaminergic neurons of the pre-frontal cortex (Jackson & Moghaddam, 2001). Raised cortisol levels have been shown to stimulate the outer shell of the nucleus accumbens. This resulted in a heightened motivation for reward gratification (Peciña, Schulkin, & Berridge, 2006). From these studies it becomes apparent that the nucleus accumbens and amygdala function in opposition to each other (mutually antagonistic). Thus while the activated nucleus accumbens gives rise to enhanced subjective gratification, it also suppresses amygdala activity and hence anxiety (Bewernick et al., 2010). The activated amygdala in turn suppresses the dopaminergic activity in the nucleus accumbens and hence the sense of gratification by stimulating pre-frontal inhibitory projections to the nucleus accumbens. The increased cortisol levels resulting from anxiety as supported by the amygdala, stimulate the outer shell of the nucleus accumbens, thereby heightening the motivation for reward and gratification.

Identifiable emotional configurations and motivation

In a partial nurture deprivation situation, the following determining factors are presumed to exist: In utero maternal cortisol levels are moderately raised. The new born infant has raised cortisol levels with the partial nurture deprivation maintaining the raised cortisol levels. This triggers the amygdala, which manifests a subjective sense of fear. The connection to the sympathetic nervous system controlling area (locus ceruleus) integrates the physiological manifestation of fear (rapid pulse rate, breathing rate, sweating). The amygdala also stimulates the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which ultimately results in a rise in the cortisol level, thus perpetuating the background fear dynamic. (The locus ceruleus has also been shown to stimulate the paraventricular nucleus.) With heightened stimulaton of the amygdala, fear may progress to anger and/or to panic. Both these states are mediated by a sympathetic nervous system raised to a higher level of function.

When the infant’s nurture needs are met and gratification is experienced, the nucleus accumbens is triggered and dopamine levels rise. It is the degree of nucleus accumbens activation that drives the infant to seek further gratification of needs when they arise. The needs-fear-gratification dynamic is integrated in the pre-frontal cortex. Also integrated in the pre-frontal cortex is the motor/movement function, which supports the physical effort of approaching closer to the nurture source. Dopamine plays a major part as the primary neurotransmitter in this process, with noradrenalin being a secondary neurochemical mediator. Therefore, from the partial nurture deprivation situation arises an individual prone to fear as well as anger/panic, but highly motivated by reward and gratification of prevailing needs. Reward and gratification has generally been experienced, albeit that this was somewhat delayedfrom time to time.

In a marked nurture deprivation situation, the following dynamic is recognizable: Excessive in utero cortisol production occurs. This sensitizes the fetal amygdala. The new born infant has significantly raised cortisol levels, probably due to the excessive amygdala stimulation and subsequent paraventricular nucleus triggering. This manifests as heightened fear/panic, which triggers the sympathetic nervous physiology. As a result of the poor nurture response, this infant experiences unfulfilled gratification for prevailing needs (which are excessive). The chronic absence of gratification results in diminished activity of the nucleus accumbens, with decreased dopamine secretion. The integration in the pre-frontal cortex is one of futility and despair for unmet needs despite the efforts exercised in this regard. Low gratification also leads to diminished motor activity, resulting in an overall situation of poor motivation. In psychological terms, this syndrome has been described as hopeless-helpless. This refers to individuals who experience a marked absence of meaning and purpose in their lives and who feel that the situation is unchangeable, unmanageable and futile. The latter state incorporates poor self-esteem, which is a further manifestation of the extreme nurture deprivation and the futility of experiencing gratification of needs. The chronicabsence of gratification leads to anhedonia. These individuals have been shown to have lower levels serotonin and dopamine (Raison, Capuron, &Miller, 2006). Decreased levels of serotonin are associated with depression and anxiety.

In an attempt to experience some gratification, the individual who is a product of severe deprivation may turn to activities that stimulate the nucleus accumbens and dopamine production and thereby provide a degree of pleasure and gratification. This includes excessive exercising, eating and smoking, or the use of such drugs as cocaine, opiods and amphetamines. The tendency to addiction results from the need to chronically stimulate the nucleus accumbens and dopamine production. From a neuropsychological perspective, the mind state that has been shown to be associated with consistently raised dopamine levels is one characterized by purposefulness, a sense of achievement or anticipated achievement and one of autonomy. Raised levels of noradrenalin, together with dopamine within a narrow range, contribute to optimal motivation, concentration, working memory and other pre-frontal cortex executive functions (Arnsten, 2009). However, excessively raised levels of noradrenalin and dopamine disrupt pre-frontal cortex, executive function. The disruption of executive function results in a shift from reflective and insightful pre- frontal activity to the reflexive fight or flight activity of the amygdala.

The configuration of decreased serotonin and dopamine, with raised noradrenalin, is associated with the secretion of raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosing factor α) by the immune system macrophages (Raison, Capuron, &Miller, 2006).

Chronically raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines also occur in the presence of chronic infection/ inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines circulate back into the brain where they affect several areas of function:

1. They induce sickness behavior—a state characterized by lethargy and poor motivation, anorexia, lack of libido and low grade fever. This situation pre- disposes to a subjective mind state of hopeless-helpless.

2. They increase the levels of cortisol by diminishing the sensitivity of the paraventricular nucleus to circulating cortisol (In the normal situation, high cortisol levels decrease paraventricular nucleus activity thus lowering cortisol levels in a negative feedback loop). Peripherally (in the body) raised cortisol levels contribute to diminished cell-mediated immunity.

3. They further diminish the levels of dopamine and serotonin levels (Miller, 2009).

4. They disrupt hippocampal functioning and thus short term memory. In time, cell loss may occur within the hippocampus with resultant hippocampal atrophy. This situation hasbeen shown to be associated with a higher incidence of developing Alzheimer’s disease in later years (Henneman, 2009; Leonard, 2007).

5. Chronically low levels of dopamine appear to predispose an individual to Parkinson’s disease, a motor disease characterized by the degeneration of dopamine producing neurons. These individuals also develop poor motivation and, in certain cases, dementia. Dopamine levels have been shown to decrease with advancing age, which further aggravates the effects of chronically raised pro-inflammatory cytokines. A reciprocal relationship exists in regard to levels of dopamine and serotonin. Raising levels of serotonin activity by means of serotonin agonists has been shown to decrease levels of dopamine. This occurs selectively in the nucleus accumbens but not in the nigrostriatal system, the system supporting motor function (Di Giovanni et al., 2000). It has also been shown that increased serotonin activity following the administration of the serotonin agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine leads to increased levels of cortisol (Ghaziuddin et al., 2003).

Two intrinsic physiological mechanisms exist whereby high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines may be decreased (Johnston & Webster, 2009):

1. Raised levels of cortisol have been shown to effectively decrease high concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In effect, this represents a feedback loop in that pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate high levels of cortisol.

2. Pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate vagus nerve afferents, which reflexively trigger vagal efferents. Stimulated efferent have been shown to decrease high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Persistently raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting from the neuro-chemical configuration described previously render these feedback mechanisms relatively ineffectual. However, direct vagal nerve stimulation with a paced electrode has been shown to be effective in decreasing raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

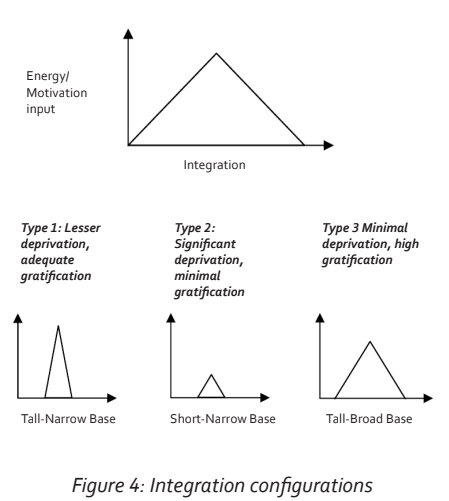

Memory, learning, storage and retrieval are influenced by emotional states and their associated levels of motivation. Lesser degrees of deprivation with adequate reward and gratification are characterized by higher levels of motivation. Even if there is a delay in a nurture response to early needs, the fact that an adequate response or reward is eventually forthcoming will justify future efforts directed at eliciting and expecting a response. Conversely higher degrees of deprivation with an inadequate response to needs are associated with lower levels of motivation because of the perceived futility of being rewarded with an adequate response. In the context of the triangular configuration of cortical integration these relationships can be represented graphically. If the vertical Y-axis represents gratification-driven motivation and the X-axis represents all aspects of labeled sensory information and associated integration, then the process of triangular integration can be depicted by a triangular configuration curve. This follows on from the fact that the higher one ascends in the hierarchy of specific representation in the cortical integration, the more specificity of representation occurs and the fewer the cell numbers. The resulting triangular graph is termed an energy-integration curve. This is illustrated in Figure 4. Three variations of this curve may be identified:

Type 1: Lesser deprivation, adequate gratification—the Bravo archetype.

This configuration has a high motivation or energy input centred upon a narrow integration base of ‘own needs’. In this situation there was a delay in response to nurture needs but ultimately this was forthcoming. A period of anxiety thus evolved during the delay period which focused attention primarily on the need to appease ‘own needs’ at the expense of a wider integration. This archetype therefore has a pre-occupation with ‘own needs’ being fulfilled, a fear that these may not be fulfilled, but an awareness that a response will invariably be forthcoming after the period of striving and fear/anxiety. There is a tendency to excessive levels of noradrenalin with an activated amygdala. The high levels of noradrenalin may shift pre-frontal activity towards inefficiency.

Type 2: Significant deprivation, minimal gratification—the Charlie archetype.

This configuration is again centred upon a narrow base of ‘own needs’ but due to the poor nurture response, low levels of gratification occur. This gives rise to a perceived futility relating to any effort exerted in the attempt to obtain a meaningful response to nurture needs. Consequently the motivation level is low on the Y-axis. In this situation excessive fear has resulted in a markedly activated amygdala with resultant raised cortisol and noradrenalin. Dopamine and serotonin levels are usually low while pro-inflammatory cytokines are raised.

Type 3: Minimal deprivation, high levels of gratification—the Alpha archetype.

Here ‘own needs’ were never an issue and therefore integration is based upon a far more extensive integration. Motivation is driven more by the gratification of ongoing broad-based integration than by the gratification of ‘own needs’. In this configuration serotonin and dopamine levels are more than adequate while levels of noradrenalin tend to be low. Personal gratification is the hallmark of this profile. This archetype generally has lower levels of noradrenalin which may impact negatively on motivation.

These three curves/archetypes form the basis of the Triangles Model which was developed by the author as a way of accessing the chemistry of wellness and performance. The application is fully quantifiable by means of an online diagnostic program (Weinberg, 2009).

Discussion

The proposed model of the human brain that emerges from a review of ongoing studies is one that integrates multiple disciplines of intervention. As our understanding of neurological processes expands, it becomes evident that neuro-anatomy and neuro-physiology (incorporating neuro-chemistry) are supportive of and in fact unify the full spectrum of neuro-psychology and neuro-endocrinology. The multiple disciplines that have contributed to the development of this model also derive from it. Specific modalities of intervention obviously reflect unique interest areas. However, understanding and accepting this new holistic neurological model will lead to greater levels of collaboration between the disciplines, which would ultimately enhance the quality of intervention.

Memory, emotion, immunity and general body metabolism are intimately connected at the level of fundamental neurophysiology. Consequently, our thoughts and feelings impact upon our bodies, the internal environment, as well as upon the external environments in which we find ourselves. But with this action comes a reaction. All processes generate feedback loops that positively or negatively impact upon the neurophysiology at source. In this regard, we note that lowered levels of dopamine and serotonin are associated with raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which in turn circulate through the brain and further lower the levels of dopamine and serotonin. This situation negatively impacts memory, predisposes individuals to sickness behavior, anxiety and depression and leads to raised levels of cortisol (Raison, Capuron, &Miller, 2006). Raised levels of cortisol sensitize the amygdala, which sustains both anxiety as well as raised cortisol.

The fundamental human drive is motivated by gratification and pleasure. When this is experienced, our levels of function in terms of mentation, general metabolism and immunity are greatly enhanced. The greatest impediment to achieving lasting gratification, however, rests with inherited deprivation influences. The challenge therefore is to engage this heritage and to neutralize its negative influences by embracing a multi-modality approach. In thecontext of intervention it should be remembered that while negative physiological processes conspire against us, positive processes, once engaged, promote and perpetuate enhancement at multiple levels.

Click here to see part two - Accessing the chemistry of consciousness and emotion.

Ian Weinberg is a practicing neurosurgeon who applies psychoneuroimmunological (PNI) principles in the clinical and corporate environments. He has also developed an online psychometric (diagnostic) which is used to evaluate individuals in the context of the application. The application is referred to as The Triangles Model, the origins of which date back to 1992. The application is used in the training of accredited coaches and is also CPD accredited for the training of medical and para-medical graduates. Workshops are routinely given in the corporate environment, as well as in clinical and personal spheres.

References

Amunts, K., Kedo, O., Kindler, M., Pieperhoff, P., Mohlberg, H., Shah, N., Habel, U., Schneider, F., & Zilles, K. (2005). Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: Intersubject variability and probability maps. Anatomy and Embryology (Berlin), 210, (5-6), 343–52.

Arnsten, A.F.T., (2009).Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortexstructure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10, 6, 410–422.

Bewernick, B.H., Hurlemann, R., Matusch, A., Kayser, S., Grubert, C., Hadrysiewicz, B., Axmacher, N., Lemke, M., Cooper-Mahkorn, D., Cohen, M.X., Brockmann, H., Lenartz, D., Sturm, V., &Schlaepfer, T.E. (2010). Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry, 15, 67, 2, 110-116.

Chrousos, G.P., & Gold, P.W. (1998). A Healthy Body in a Healthy Mind and Vice Versa. TheDamaging Power of “Uncontrollable” Stress. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83, 6, 1842-1845.

Coplan, J.D., Andrews, M.W., Rosenblum, L.A., Owens, M.J., Friedman, S., Gorman, J.M., & Nemeroff, C.B. (1996). Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-lifestressors: Implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93, 1619-1623.

Davachi,L., & Dobbins, I.G. (2008). Declarative Memory. Association for Psychological Science, 17, 2

Di Giovanni, G., Di Matteo, V., Di Mascio, M., & Esposito, E. (2000). Preferential modulationof mesolimbic vs. nigrostriatal dopaminergic function by serotonin(2C/2B) receptoragonists: a combined in vivo electrophysiological and microdialysis study. Synapse, 35, 1, 53-61.

Felleman, D.J., & Van Essen, D.C. (1991). Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 1, 1-47.

Ganong, W.F. (1979). Review of Medical Physiology. 9th Ed. Lange. Los Altos, 99-100.

Ghaziuddin, N., Welch, K., & Greden, J. (2003). Central serotonergic effects of m-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) among normal control adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 133–139.

Gorman, J.M., Kent, J.M., Sullivan, G.M., & Coplan, J.D. (2000). Neuroanatomical hypothesisof panic disorder, revised. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 4, 493-505.

Henneman, W. (2009). Hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer disease: added value overwhole brain volume measures. Neurology, 72, 999-1007.

Jackson, M.E., & Moghaddam, B. (2001). Amygdala Regulation of Nucleus Accumbens Dopamine Output is Governed by the Prefrontal Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 2, 676–681.

Jessell, T.M., &Sanes, J.R. (2000). The decade of the developing brain. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 10, 599–611`

Johnston, G.R., & Webster, N.R. (2009). Cytokines and the immunomodulatory function of the vagus nerve. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 102,4, 453-62.

Kandel, E.R. (2001). The Molecular Biology of Memory Storage: A Dialogue BetweenGenes and Synapses. Science, 294, 1030-1038.

Jung-Beeman, M., Bowden, E.M., Haberman, J., Frymiare, J.L., Arambel-Liu, S., Greenblatt, R., Reber, P.J., & Kounios, J. (2004). Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. PLoS Biology, 2, 4, 500-11

Kandel, E.R. (2001). The Molecular Biology of Memory Storage: A Dialogue Between Genes and Synapses. Science, 294, 1030- 1038.

Keating, E.G., & Horel, J.A.(1972). Effects of prestriate and striate lesions on performance of Simple visual tasks. Experimental Neurology, 35, 2, 322-336.

Leonard, B.E. (2007). Neurodegeneration: the link between depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurologia Croatica, 56, 5, 51-55.

Maguire, E.A., Gadian, D.G., Johnsrude, I.S., Good, C.D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R.S., & Frith, C.D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 8, 4398–403.

McEwen, B.S. (1998).Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338,171–179.

Miller, A.H. (2009). Mechanisms of cytokine-induced behavioral changes: Psychoneuroimmunology at the translational interface. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23, 149–158.

Olds, J., & Milner, P. (1954). Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 47, 6, 419–27.

Packard, M.G., & Knowlton, B.J. (2002). Learning and memory functions of the Basal Ganglia. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 25, 563-593.

Peciña, P., Schulkin, J., & Berridge, K.C. (2006). Nucleus accumbens corticotropin-releasing factor increases cue-triggered motivation for sucrose reward: paradoxical positive incentive effects in stress? Biomedical Central Biology, 4,8.

Percheron, G. (2003). Thalamus. In Paxinos G., and May J.,(eds). The human nervous system. 2d Ed. Elsevier. Amsterdam, 592-675.

Raison, C.L., Capuron, L., &Miller, A.H. (2006). Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends in Immunology, 27, 1, 24–31.

Si, K., Lindquist, S. & Kandel, E.R.(2003). A neuronal isoform of the Aplysia CPEB has prion-like properties. Cell, 115, 879–891.

Tarullo, A.R., & Gunnar, M.R. (2006). Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior, 50, 632–639.

Van den Bergh, B.R., Mulder, E.J., Mennes, M., & Glover, V. (2005). Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioral development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 29, 2, 237-58.

Weinberg, I. (2009). Accessing the Chemistry of Wellness and Performance. Neuroleadership Journal, 2, 85-93.

Zahm, D.S. (2000). An integrative neuroanatomical perspective on some subcortical substratesof adaptive responding with emphasis on the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24, 85–105.

Ian Weinberg is a practicing neurosurgeon who applies psychoneuroimmunological (PNI) principles in the clinical and corporate environments. He has also developed an online psychometric (diagnostic) which is used to evaluate individuals in the context of the application. The application is referred to as The Triangles Model, the origins of which date back to 1992. The application is used in the training of accredited coaches and is also CPD accredited for the training of medical and para-medical graduates. Workshops are routinely given in the corporate environment, as well as in clinical and personal spheres.

Important: TherapyRoute does not provide medical advice. All content is for informational purposes and cannot replace consulting a healthcare professional. If you face an emergency, please contact a local emergency service. For immediate emotional support, consider contacting a local helpline.

Creating Space for Growth: How Boundaries Strengthen Relationships

Setting boundaries in relationships is one of the most important yet often overlooked aspects of maintaining healthy connections with others. Boundaries are personal limi...

International Mutual Recognition Agreements for Mental Health Professionals

Table of Contents | Jump Ahead Executive Summary Part I: Bilateral Agreements Part II: Multilateral Frameworks Part III: Profession-Specific Frameworks Part IV: Assessmen...

Jumping to Conclusions

Table of Contents Definition Key Characteristics Theoretical Background Clinical Applications Treatment Approaches Research and Evidence Examples and Applications Conclus...

Case Conceptualisation

Table of Contents Definition Key Characteristics Theoretical Background Clinical Applications Conceptualisation Process International Perspectives Research and Evidence P...

Guided Discovery

Table of Contents Definition Key Characteristics Theoretical Background Clinical Applications Treatment Applications Research and Evidence Techniques and Methods Professi...

About The Author

New Therapist Magazine

Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

“An independent, subscription-based magazine for mental health therapists, produced by journalists and therapists on five continents.”

New Therapist Magazine is a qualified , based in Clarendon, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. With a commitment to mental health, New Therapist Magazine provides services in , including . New Therapist Magazine has expertise in .

Author More Articles

The Dialogical Cure: An interview with Hubert Hermans

, , South Africa, Pietermaritzburg

A Sense of Selves

, , South Africa, Pietermaritzburg

Body of Evidence

Kelly Quayle, , South Africa, Pietermaritzburg

Minding the Body

Trish Bartley, , South Africa, Pietermaritzburg

Related Articles

Brain Health

Your brain powers every thought, movement, and emotion, but its health is shaped by daily choices more than most people realise. Read on to explore what brain health real...

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback trains your brain using real-time feedback to improve focus, reduce stress, and support mental well-being. Read on to learn how it works, who it can help, a...

Brain’s Biological Age Predicts Longevity

Thee lifestyle tips help you keep your brain and immune system young